A Respectful but Firm Rebuttal of a Faulty VAT Narrative:

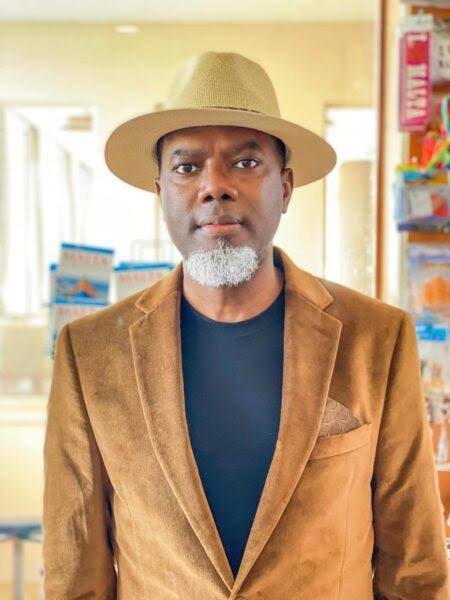

By Barrister Joseph Obinna Aguiyi

The recent intervention by Mr. Osita Chidoka on the subject of VAT contribution and distribution in Nigeria, though couched in the language of technocracy and statistics, unfortunately descends into what can best be described as a xenocentric and reductionist analysis of the South-East economy. While Mr. Chidoka insists that “VAT does not follow the trader; it follows the state,” he simultaneously refuses to interrogate why the trader, the enterprise, the vehicle, the factory, and even the multinational headquarters are structurally and coercively displaced from their natural economic homes. Statistics without context are not truth; they are at best incomplete, and at worst, instruments of intellectual misdirection.

This essay does not deny the arithmetic of VAT tables as published by federal institutions. Rather, it challenges the epistemology behind Mr. Chidoka’s conclusions, the selective blindness to history, power, coercion, and human behavior that renders his analysis academically unsafe and socially corrosive.

1. The False Isolation of the South-East from the Old Eastern Economic Bloc

One of the gravest flaws in Mr. Chidoka’s argument is his deliberate isolation of the South-East from the former Eastern Region economic equation. Prior to military centralisation, the Eastern Region functioned as an integrated economic unit, with ports, railways, industries, and agricultural value chains deliberately spread across the region. The post-war Nigerian state dismantled this structure through constitutional centralisation, seizure of ports, railways, power, and fiscal levers via the Exclusive Legislative List.

To isolate the South-East today, while folding Lagos—a former separate colony and later a perpetual federal capital territory—into the South-West without qualification, is an analytical fraud. Lagos has enjoyed over a century of concentrated federal presence, infrastructure, port access, customs headquarters, multinational clustering, and security prioritisation. Comparing VAT outcomes between a structurally pampered city-state and a deliberately constrained inland region without ports, rail, or power is not economics; it is theatre.

2. Investment Determines Tax Outcomes — A Variable Chidoka Avoided

Mr. Chidoka refused to compare federal and private investment inflows across regions before drawing conclusions about VAT performance. VAT is not manna from heaven; it is the residue of structured investment, logistics, power supply, and regulatory protection.

Where are Nigeria’s major ports? Lagos. Where are the customs command centres? Lagos. Where are most multinational headquarters domiciled by coercion or convenience? Lagos. Where are federal roads, rail lines, and power redundancies concentrated? Lagos and the Abuja axis.

To ignore this and then declare the South-East a “net beneficiary” is akin to starving a man, breaking his legs, and then mocking him for not winning a marathon.

3. Demographics: The Foot Soldiers of VAT Were Ignored

VAT is paid by people, not abstractions. Traders, transporters, consumers, SMEs, telecom subscribers, and import-dependent households are the foot soldiers of Nigeria’s VAT economy. Mr. Chidoka refused to interrogate the demographic truth that South-Easterners disproportionately populate commercial activity across Nigeria, especially in Lagos and Abuja.

Nigeria does not produce; it consumes. VAT is therefore consumption-driven, not production-driven. Who are the consumers sustaining telecom VAT, import VAT, transport VAT, and retail VAT across Lagos markets, motor parks, malls, and warehouses? This human variable was completely absent from Mr. Chidoka’s calculus, rendering his analysis sociologically hollow.

4. Systematic Highway Harassment and Forced Economic Migration

Perhaps the most dishonest silence in Mr. Chidoka’s essay is his refusal to acknowledge the systematic harassment of South-East registered vehicles on Nigerian highways. For decades, vehicles bearing South-East plate numbers have been treated as quarry specimens—extorted, delayed, criminalised, and endangered by multiple law-enforcement tollgates.

The rational response of any economic actor is survival. Businesses therefore relocated registration, headquarters, fleets, and compliance domiciles to Lagos and Abuja to avoid harassment. This single coercive behavior alone artificially inflated the domicile tax profile of the South-West and the FCT.

To then turn around and weaponise VAT data produced by this coercion against the victims is the height of intellectual hypocrisy.

5. Onitsha, Lagos Registration, and Regulatory Bullying

Onitsha remains one of the largest commercial nerve centres in West Africa by volume of trade. Yet thousands of businesses operating physically in Onitsha are registered in Lagos. Why?

Because regulatory agencies—FIRS, Customs, SON, NAFDAC, police task forces—have historically used Onitsha and Aba as punishment zones rather than commercial partners. Multiple taxation, arbitrary closures, criminalisation of inventory, and extortion forced SMEs to formalise elsewhere.

Mr. Chidoka knows this. His refusal to state it is not ignorance; it is omission by design.

6. Age, Opportunity, and Weaponised Constitutional Centralism

States are not born equal. Lagos has enjoyed uninterrupted federal favour since colonial times. The South-East emerged from a genocidal war, reconstruction without restitution, abandoned infrastructure, and a constitution that weaponised the Exclusive List to strip regions of power over ports, rail, electricity, policing, and minerals.

VAT outcomes are therefore predetermined by constitutional design, not entrepreneurial deficiency. To pretend otherwise is to confuse consequence with cause.

7. Security as an Economic Determinant

Insecurity in the South-East did not emerge in a vacuum. It has been aggravated by deliberate under-policing, militarisation without development, and economic strangulation. Businesses respond rationally: they relocate capital, staff, and registration to safer zones. VAT follows safety. Mr. Chidoka omitted this inconvenient truth.

8. On the Use of Government Statistics

Finally, Mr. Chidoka’s uncritical reliance on government statistics—produced by institutions notorious for non-empirical methodologies—further weakens his argument. Data divorced from context is not scholarship. Any academic work that ignores human behavior, coercion, history, and political economy is emotive, not empirical.

Conclusion: A Rejection of Hypocritical Posturing

This essay respectfully but firmly rejects Mr. Chidoka’s posturing. His analysis, while numerically neat, is intellectually incomplete and ethically troubling. It should not be cited for academic purposes without heavy qualification.

The South-East’s contribution to Nigeria’s tax economy cannot be reduced to VAT tables divorced from history, coercion, demographics, and structural discrimination. VAT does not merely “follow the state”; it follows power, safety, infrastructure, and freedom from harassment.

Until Nigeria confronts these truths honestly, any regional VAT comparison will remain what Mr. Chidoka’s essay ultimately is: a selective narrative masquerading as objective analysis.

A Respectful but Firm Rebuttal of a Faulty VAT Narrative: By Barrister Joseph Obinna Aguiyi

Leave a Reply